“Autumn is a second spring when every leaf is a flower.”

– Albert Camus

Erika Nichols-Frazer is the author of the essay collection “Feed Me” (Sept. 2022, Moonlight Books) and the forthcoming poetry collection “Staring Too Closely” (Main Street Rag, 2023). She is he editor of the mental health recovery anthology “A Tether to This World” (Main Street Rag, 2021). She won Noir Nation’s 2020 Golden Fedora Fiction Prize and has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. Her work has appeared or is forthcoming in Gone Lawn, River Teeth’s Beautiful Things, Emerge Literary Journal, Idle Ink, and elsewhere. She has an MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars and lives in Vermont, U.S.A.

Why I Speak to Trees

The scythe of a crescent moon

cuts shadows on my collarbone.

Night undresses me with

ten thousand pools of light.

An army of stars burns.

Branches peel mist

and unveil evening.

Plummeting leaves howl

against wind

in a language

only I can translate

you are smaller than you appear

Your grief will be a rudder slicing through murk.

No one, save you, knows its shape.

Another day, you would have seemed younger.

Your grief is deciduous,

returning faithfully after each climactic fall,

a constant against which to measure yourself.

I do not know your pain. I am a stranger here,

as you were, once.

Neither of us sleeps, I know.

Your grief a splint of metal, cold on skin,

held in place by wood softened with weather and age,

that leaves a mark and the muscle a little weak

no one can see it but you and me;

we speak the language of grief.

Your pain is smaller than it appears.

The Babushkas of Chernobyl

they call the grandmothers who

lived their whole lives in Chernobyl

and refused to leave after the nuclear disaster.

Even after evacuation, the babushkas returned.

The government tried to evacuate them again,

but Chernobyl was the only home they’d ever had.

They planted their feet in poison earth.

They swigged moonshine and swallowed

thick slices of hog fat, their gardens barren

in toxic soil. They stayed.

I want to know what it tastes like

to love a place like that, to have a home

to suffer for.

Digging for Cassava

Nancy, the farmer’s daughter, and I dig

for cassava, our knees in red earth.

Even now, in the fields, she wears

a crisp yellow button-up dress,

as if she is ready for school.

As our hands, stained red, pull cassava

from the ground and stack them in our

baskets, she says she wants to be a writer, too.

When I leave, she gives me a Polaroid of her

in her school clothes, looking serious,

with her address on the back.

For months after I return from Ghana,

while I begin college, I write to her and

send her my childhood books.

She tells me she doesn’t have any books

in her house, but she knows how to dig.

When you sleep

Your pelvis cuts a shadow

sharp as an oyster shell,

inviting my arm to slip and

hang, a full sail of skin

under your hip bones.

When you sleep I drape

my dreams on your shoulder

blades and slip fear over

your eyes, tucking you in

for a long night.

When you sleep your skin

whispers confessions to me.

When you sleep my breath

tells you fairytales, spinning

myths from my name.

When you sleep your eyelids

converse in flickers like the bare

lightbulb hanging in our closet,

daring me to answer.

My cheekbones snug in your clavicle:

You are more honest then.

Nadia Arioli is the co-founder and editor in chief of Thimble Literary Magazine. Their recent publications include Penn Review, Hunger Mountain, Cider Press Review, Kissing Dynamite, Heavy Feather Review, and San Pedro River Review. They have chapbooks from Cringe-Worthy Poetry Collective, Dancing Girl Press, Spartan, and a full-length from Luchador. They were nominated for Best of the Net in 2021 by As It Ought to Be, West Trestle Review, Angel Rust, and Voicemail Poems.

Salt and Pomegranates

I.

Fish are a kind of fruit,

in the land of scribble and belly.

Rotting in the Lethe, the

scales catch the half-light,

the bones from which the next

crop springs. Here, death hatches.

Two figures meet without

ceremony. The taller says

Here, we only gesture at organic

forms, but still it hurts to look.

The smaller says There is no turning,

back or otherwise. To turn

implies a change, and in

eternity, we cannot attempt a spin

or any kind of risk.

In my defense, the taller says,

I had to be sure. To be sure,

the smaller says, I had to defend

my agency. Yours is the

tragedy, mine was only foolishness,

and fools aren’t even given names.

I could give you one, says the taller,

trying still to enchant. I can put

it into song. The smaller

says nothing. Could I call you

Euridice? The smaller gives

no reply, but reaches in water and

and plucks a fish. She peels

the skin with her claws. She

brings yellow eye to outline

eye. Now we’re both dead.

Looking can be a no.

Salt and Pomegranates

II.

Fish are a kind of fruit,

in the land of scribble and belly.

Rotting in the Lethe, the

scales catch the half-light,

the bones from which the next

crop springs. Here, death hatches.

Two figures meet without

ceremony. The taller says

Here, we only gesture at organic

forms, but still ithurtstolook.

The smaller says, There is no turning,

back or otherwise. To turn

implies a change, and in

eternity, we cannot attempt a spin

or any kind of risk.

In my defense, the taller says,

I had to be sure. To be sure,

the smaller says, I had to defend

my agency. Yours is the

tragedy, mine was only foolishness,

and fools aren’t even given names.

I could give you one, says the taller,

trying still to enchant. I can put

it into song. The smaller

says nothing. Could I call you

Euridice? The smaller gives

no reply, but reaches in water and

and plucks a fish. She peels

the skin with her claws. She

brings yellow eye to outline

eye. Now we’re both dead.

Looking can be a no.

Salt & P(o)megranates

IIII.

Fish (are a kind of fruit)

in the land of scribbleandbelly.

Rotting in the L e t h e, the

scales catchthehal-flight,

the bones from which the next

crop springs. Here, death h a t c h e s.

Two figures meet without

ceremony. The taller says

Here, we only (((((gesture)))) at organic

forms, but still it hurts to look.

The smaller says There is no t/u/r/n/i/n/g,

back or othe,rwise. To t,u,r,n

implies a <change, and in

eternity, <we cannot attempt a sp!n

or any kind,,,of,,,risk.

In my de[fense, the taller says,

I had to be sure]]. To be sure,

the smaller says, i had to defend

my agency. …Yours is the

tragedy,,,, mine was only foolishness,

and fools arent even given names.

I could,, give you one, says the taller,

trying still to enchant. I can put::::

it into song. The smaller

says nothing. <<<Could I call you

Eur(i)d(i)ce? ?The smaller gives

no reply, /but reaches in water/ and

and plucks a fish. She p e e l s

the skin with her c<l<aws. She

b r i n g s yellow eye to outline

eye. Now we’re both dead.

L o o king can be a no.

Allan Lake once lived in Allover, Canada but now lives in Allover, Australia. Coincidence. His

latest chapbook of poems is called My Photos of Sicily and was published by Ginninderra Press. It contains only poems, no photos.

Lift

Divine plum danish

from Baba Bakery, then coffee

at Cafe Baal, which was awash

with joyous Brazilian bossa.

An unlikely confluence in this

punk, plastered, bat-infested

Australian city but the trinity

aligned and my gloom just

e v a p o r a t e d

like mid-morning fog

that finally remembered

it’s sunny way home after

a fruitless night out.

Michael J. Leach is an Australian academic and poet based at the Monash University School of Rural Health. His poems reside in Rabbit, Cordite, Meniscus, Verandah, Plumwood Mountain, Live Encounters, the Medical Journal of Australia, the 2021 Hippocrates Prize Anthology, and elsewhere. Michael’s poetry collections include Chronicity (Melbourne Poets Union, 2020) and Natural Philosophies (Recent Work Press, forthcoming). He lives on unceded Dja Dja Wurrung Country and acknowledges the traditional custodians of the land.

Morph(eme) Moments

for Jess

when I ponder

portmanteaus

I remember

seeing so many angles of Brangelina

rewatching ’80s mockumentaries

playing games of Pictionary

staying in for staycations

escaping to seascapes

analysing data with Stata

working towards workaholism

overspending on weekend brunches

reading sciku

writing scifaiku

hand feeding cloistered camelopards

cuddling COVID cavoodles

growing a mo for Movember

feeling the flow of endorphins

emoting with(out) emoticons

paying (in)attention to podcasts

tuning in/out to the Twitterverse

rewatching movies…with Muppets

seeing so many new-gen Brangelinas

I remember

portmanteaus

when I ponder

Domnica Radulescu is a Romanian American writer who arrived in the United States in the early eighties as a political refugee. She settled in Chicago where she obtained a PhD in Romance Languages from the University of Chicago in 1992. Radulescu is the author of three critically acclaimed novels, Train to Trieste (Knopf 2008 &2009), Black Sea Twilight (Transworld 2011 & 2012) and Country of Red Azaleas (Hachette 2016), and of award-winning plays. Train to Trieste has been published in thirteen languages and is the winner of the 2009 Library of Virginia Fiction Award. Radulescu received the 2011 Outstanding Faculty Award from the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia. Radulescu also published fourteen non-fiction books, edited and co-edited collections on topics ranging from the tragic heroine in western literature to feminist comedy, to studies of exile literature and two collections of original plays. Dream in a Suitcase. The Story of an immigrant Life is her first memoir, and it was released in January 2022. Radulescu is twice a Fulbright scholar and the founding director of the National Symposium of Theater in Academe.

Stella Vinitchi Radulescu is a poet of Romanian origin living in the United States and writing in three languages: French, English and Romanian. She has published numerous volumes of poetry in France, the United States and Romania. She received numerous prizes for her poetry such as the Grand Prix Noel-Henri Villard 2008, the Amelie Murat prize in 2013 and the Great Prize of Francophone Poetry. The volume A Cry in the Snow (translated from the French) appeared with Orison Books in 2018. Her latest two volumes of poetry are Traveling with the Ghosts (Orison Books 2021) and Vocabulaire du silence (Editions du Cygne 2022)

Poems from Vocabulaire du Silence (Vocabulary of Silence), by Stella Vinitchi Radulescu

Translated from the French by Domnica Radulescu

les nuits sont calmes sur ma langue

les jours gelés

et en sourdine les vagues déplacent

les mondes

comme grains de sable

rien ne bouge

de ce côté

la page reste telle :

ensanglantée

une lettre monte

au ciel

une autre descend

l’enfer au bout

de mes

doigts

point fixe—

autrement

blancheur

l’encre

se dissipe

phrases non-dites

: je m’accroche

à ce vide

poème poème

intrusion

dans

le vide porte ouverte

porte fermée

d’où

sortent

ces flammes et

qui est là

pour

ramasser

les cendres

désabille-toi nuit de ta

noirceur fille

adultère d’un soleil disparu

mille ans de chaque

côté de ce désert — accouche

lumière dans les parages

de l’oubli

nos chants terrestres montent

au ciel les arbres s’agenouillent

et prient

musique la pluie

bavarde sur le toit telle

enfance

je m’endors

dans l’autre temps l’autre

pays où les nuits

sont plus longues nuits

de velours

et les aubes s’attardent :

cette page s’ècrit

à rebou

the nights are peaceful on my tongue

the frozen days

and muted waves displace

the worlds

like grains of sand

nothing moves

on this side

the page stays bloody

as it is

a letter soars

to the sky

another descends

hell

at

my fingertips

steady point –

otherwise

whiteness

the ink dissolves

unspoken sentences

: I am clinging

to this void

poem poem

intrusion

in

the void open door

closed door

from where

emerge

these flames and

who is there

to gather

the ashes

undress yourself night of your

darkness adulterous daughter

of an extinct sun

a thousand years of each

side of this desert – you light

give birth

close to oblivion

our terrestrial songs soar

to the sky the trees are kneeling

and are praying

music the rain

is talking on the roof such

childhood

I fall asleep

In the other age the other

country where the nights

are longer

velvet nights

and the dawns linger:

this page writes itself

backwards

Patricia Walsh was born and raised in the parish of Mourneabbey, Co Cork, Ireland. To date, she has published one novel, titled The Quest for Lost Eire, in 2014, and has published one collection of poetry, titled Continuity Errors, with Lapwing Publications in 2010. She has since been published in a variety of print and online journals. She has also published another novel, In The Days of Ford Cortina, in August 2021.

Reluctant Recidivist

Slow to commit any form of crime

Faithfully deported to suitable lodgings

Hunting heads of the conscientious consumed

Matching like to like, as a jigsaw.

Not a race, therefore not racist. What I would give

For a standard textbook to judge others by!

Forget the stereotypes, bleached to the root

Vainglorious in circumstance tempers the cold.

Coat drenched on another’s chair

Dancing in time to a foreign clap

Eating meat, prayer, upon, consuming

With a wounded conscience looming small.

The days lengthen by degrees.

Controlled fasting becomes the determined.

Determined in eyes of the god of hosts

Killing as if we make an educated mistake.

Picking the chicks in a submerged ballroom

Where no light can escape, cross upon back

A journey towards salvation, a criminal’s death

Singing towards home, oblivious to danger.

Not my will, but yours. Killing the solution

If you’re not part of the problem, so what?

Green on red colors the recidivist spirit

An acreage of beauty redeemed for others.

All-Over Rash

Spilling vinaigrette, a hard or soft option

Renting a cause to consummate anger

A favorite to be upheld, never wavering.

Limerick Junction is closer to the mark

Burning kisses in an opportune mind

Sinking drinks denied to others.

Fear of women pervades the decorum

Of proper order, a coupling annexed

Watching for outside conquering.

A woman playing with fire stands erect

Eschewing caution in a hair’s breadth

Slipping kisses into drinks, procreative times.

Nothing, if not critical. Sinking into rivers

Tests your patience and social outlets.

A wasted exercise in compassion, after all.

Some white widow sledgehammers the day

A prisoner of purgatory bangs on the door

Seeking release from caring for fellow beings.

Splitting hairs, seconds, making a killing

Out of enjoyed events unencumbered by tears

Barbed and off-limits to the unwary.

Sleeping in a foreign bed, consummating need

Friendly invitations fall flat by persuasion

No option declaring your divine right.

Thomas Piekarski is a former editor of the California State Poetry Quarterly. His poetry has

appeared in such publications as Poetry Quarterly, Literature Today, The Journal, Poetry

Salzburg, Modern Literature, South African Literary Journal, Home Planet News, and others.

His books of poetry are Ballad of Billy the Kid, Monterey Bay Adventures, Mercurial World, and Aurora California.

City Nocturne

I’m going to have it my way this time. It’s my turn.

What I see or feel can’t be quantified. Some themes

no longer resonate. I cook up metaphors and tropes

then tie them together with an invisible bow. Surely

blood pulsing through the brain allows me to form

an ambient environment in which to lay my claims.

I was there once other than in a dream. That place

since hidden comes gushing as words proliferate.

Laden with possibility spontaneous synchronicity

spurts out images in most unpredictable phrases.

Streetlights glare within fog-infused atmosphere.

Like ice melting darkness slides on greased rails.

Fuzzy night, memories loom, I lift my collar as

a cable car disappears over the hill in dank mist.

Stanzas take shape on my tabula rasa. Next to

the street sign lovers embrace, rapt amazement

as lips lock in a long kiss. The foghorn doesn’t

disturb the flight of gulls cavorting in liquid air.

Oblivious am I to passersby and beaming cherry

that spins on a cop car’s steel roof as it sizzles in

suffused luminescence. Skyscrapers stretch way

to heaven. I’m not in the Louvre and won’t drink

from an imagined fountain of youth I tell myself,

for too many lives are spoiled by excessive folly.

Below the surface lost Atlantis may be located.

The city abides me, it has seen countless lovers

during generations of its rollicking intoxication.

Waves swish up against the ghostly ferry’s sides.

The poem hasn’t coalesced yet but getting there,

just needs a little stirring and maybe savoir faire.

The moon yawns and from its wide mouth leak

shadows of tomorrow morning. Laughter streams

out of an apartment window as saxophone music

proliferates down a narrow alley. New love chips

away at calcified hearts. Revision is unnecessary

since a final draft appears to me clearly focused.

Divertimento

Sublimity and love merge,

a river that always flows

not fast, not slow,

never too high nor low.

At the delta lagoon

grown green with algae

a lone fisherman casts

from atop the levee.

It’s high noon in Dodge,

traffic a lamentable bog

has locals disconnected

from all but problems.

Rude conspiracies clash

with verifiable fact

gushing streams

of spooky anarchy.

At his apogee of fame

the failed general leapt

from seventeen stories,

landed with a splat.

This river will tame

the wild, heal the lame.

Just give it time,

it doesn’t drain.

Potential catastrophe,

panic and dislocation

if too much Greenland ice

cracks off, floats away.

Nothing more to say

about that except

for hip-hip hooray

the gang’s all here.

Leonard Tuchilatu (1951-1975) was a Romanian poet from Moldova, one of the former soviet republics. He died of an incurable illness at the age of 24, after being subjected to multiple disciplinary punishments during mandatory army service (the ruthlessness of the soviet military abuses is infamous in the post-soviet territories). Though virtually unknown outside Moldova, the poet has gathered a following among several generations of Moldovan poets. Posthumously published work: Sol (1977), Fata Morgana (1989), the anthology Sol. Fata Morgana (1995), and the bilingual (Romanian/Russian) collection Rapsodie (2001).

Originally from Chisinau, Moldova, Romana Iorga is the author of two poetry collections in Romanian. Her work in English has appeared or is forthcoming in various journals, including the New England Review, Salamander, The Nation, as well as on her poetry blog at clayandbranches.com

Artă

În simplitatea asta a bucuriilor

oare cine te orânduiește?

Plăpând par

în tremurul unei lumânări

pe jumătate arse

și scriu despre lumină, despre bucuriile orei.

Geamătul surd însă minte atât de nerușinat…

Și mă aplec încet, încet, să culeg

grăunțele unei amărăciuni adevărate…

Art

In this simplicity

of joy, who might sort you out?

I look frail in the shudder

of a half-burnt candle

and I write about the light, about the joy of this hour.

Shameless, however, the muffled groan lies…

And slowly, slowly I lean to collect

the grains of a truer sorrow…

Durere

Mă găseşti şi aici,

învelindu-mă cum ştii numai tu,

cum numai tu o poţi face.

Mă găseşti şi aici,

mut, cunoscându-te de departe.

Cine te-a urât oare mai mult,

cine te-a căutat pentru joacă

pentru a face bravură

şi nu numai,

şi nu numai…

Tu lasă-te în urmă râzând,

cum rareori ne lăsai,

şi nu mai fi

regină a grădinilor negre

Pain

You find me here as well,

tucking me in as only you know

how, as only you can.

You find me here as well,

a mute who recognizes you from afar.

Has anyone hated you more,

has anyone sought you out to play,

to fake bravery

and not only that,

not only…

Fall behind now, laughing,

the way you seldom allowed us

to do and cease to be

our queen of the black gardens.

Ore târzii

De câte ori

m-am întâlnit cu tine, cuvânt,

de atâtea ori

am rămas atât de singur,

că-mi simţeam sufletul

cum curge din mine.

De atâtea ori am strigat

până mi-am pierdut cumpătul,

ca să ajungă lumina

şi la căpătâiul celui din urmă

muribund.

Late Hours

No matter

how often I ran into you, word,

each time

I was left so alone

that I felt my soul

draining away from me.

Each time, I shouted

until I lost all reason,

so that the light could also touch

the forehead of the last dying man.

Charline Lambert was born in 1989 in Liège, Belgium. She is the author of four books of poetry: Chanvre et lierre (“Hemp and Ivy,” Éditions Le Taillis Pré, 2016), Sous dialyses (“Dialyzing,” Éditions L’Âge d’Homme, 2016), Désincarcération (“Decarceration,” Éditions L’Âge d’Homme, 2017), and Une salve (“A Salvo,” Éditions L’Âge d’Homme, 2020).

John Taylor’s most recent translations are, from the French, José-Flore Tappy’s Trás-os-Montes (The MadHat Press) and Philippe Jaccottet’s Ponge, Pastures, Prairies (Black Square Editions), as well as, from the Italian, Franca Mancinelli’s The Butterfly Cemetery: Selected Prose 2008-2021 (The Bitter Oleander Press). He lives in France.

Toujours de cette langue

à chair de porcelaine

à tentation de falaise

en acérer

une joie de tranchant.

*

Toujours de ce corps

en volutes lascives

en délicats incarnats

en tirer

une salve d’invocations.

*

là

une salve

dedans

des esclaves

depuis

une salive

*

là

un feu fœtus

renâcle

à se dérouler

dedans

un fleuve

en son sein

des eaux insoupçonnées

depuis

devenu forêt

ce corps canalisant

ses foisonnements

*

là

la pollution

aggrave les saignées

des poignets de pierres

aux reins

dedans

le même sexe

excisé des lèvres

anéanties du poids

des lapidations

depuis

un désir élancé

immarcescible

dans la mer

*

là

le même soleil

allonge d’une lampée

cette bouffée arrachée

à la boue d’être

dedans

le vaste s’ouvre

en dorsaux où l’ample

déroule sa chair claire

depuis

le seul Soleil

ne grève les tempes

à la poussière : il pousse

à la racine d’êtres

© Une salve, Éditions L’Âge d’Homme, 2020.

from A Salvo

by Charline Lambert

translated from the French by John Taylor

Ever from this tongue

its porcelain flesh

its tempting cliff

whet

a sharp-edged joy.

*

Ever from this body

in lascivious volutes

in delicate crimsons

discharge

a salvo of invocations.

*

there

a salvo

inside

slaves

ever since

a saliva

*

there

a fetus fire

reluctant

to unroll itself

inside

a river

within whose bosom

are unsuspected waters

ever since

this body

canalizing its profusions

has become a forest

*

there

pollution

aggravates the bloodletting

from the wrists of stones

in the kidneys

inside

the same sexual organ

its lips excised

and annihilated from the weight

of the stone-throwing

ever since

an imperishable desire

leaping

into the sea

*

there

the same sun

lengthens by a gulp

this breath torn off

from the mud of being

inside

the vastness opens out

into dorsals in which ampleness

unrolls its bright flesh

ever since

the only Sun

weighs down no forehead

to the dust: it sprouts

from the roots of beings

—from Une salve, Éditions L’Âge d’Homme, 2020

Junaid Shah Shabir is a Kashmiri writer who pens both critical as well as creative pieces. He is presently pursuing his PhD at UT Dallas. His works have also emerged in Asiatic: IIUM Journal of English Language and Literature, Jaggery: A DesiLit Arts and Literature Journal, Contemporary Literary Review India, The Criterion: An International Journal in English, IJOES. Through the short fiction and poetry, that he seldom finds himself writing, he tries to speak truth to the power and bear witness to the plight of ordinary people in contemporary occupations and political conflicts.

Navel-gazing

As I shut the window in a haste,

The warm bottle, on the windowsill, slid off;

And pushed the mirror to fall.

Here it lies, smashed and splintered before my sight.

I am staring at the fragments, shards, and pieces

That have quickly worked out a maze.

Looking into the broken pieces I see shreds of my own virtual self;

Scattered, withered, and tattered.

I can’t help but draw an analogy,

An analogy of broken mirror and human abstract;

Trust – once torn is arduous to mend.

Expectations – if not met, always hurt.

Pain – left uncured, makes us diseased.

Kindness – maltreated, creates a parasite.

Understanding – if not mutual, leads to chaos.

Love – when not requited, breeds infection.

Pleasure – sought in excess, mangles the soul.

Scattered pieces derange my contemplation,

And seek back my attention.

Hapless pieces no more an entity.

Watch out! Watch out! Hold onto yourself;

For once fallen, you crumble into pieces.

Useless!

You belong to none, and no one belongs to you.

Resuscitation

And our last tête-à-tête ended

with heartbreak and hopelessness.

We both said things we didn’t mean

She wept bitterly with regret and longing,

I acted stone-hearted and spoke indifferently.

In Kashmir, they build gardens over the

rubbles of their houses – when razed to the ground.

From this, I have learnt that Explosion is not

How the story has to end!

Azadi . . .

Where woman becomes a possession and not an entity,

Where man is known by his social stature and by what he owns,

Where being knowledgeable bears you no fruits while money buys you everything,

Where society is broken into fragments and narrow domestic walls,

Where the appearance mesmerizes while the reality is not known,

The essence is not your concern while the pretense is all that matters.

Where people conform easily and less is enacted out of conviction,

Where the next-door neighbor is a stranger but the virtual one is loved,

Where fundamentalism is in air and every second person holds a tape

To measure religion on the scale of pluses and minuses,

Where materialism runs down the line and love is but a cliché,

Where pleasing people is more important than pleasing God,

Azadi there, my dear, is a long way from here.

Dana Neacşu, a New Yorker expat, currently living in Pittsburgh has translated works of fiction from Romanian into English and non-fiction from English into Romanian. She is hard at work on a collection of stories about the 1970s Romania, the first decade in the life of her young protagonist, Trey. Her nickname extols the magical number three (trei) days one needed to survive in order to be. Their name was then listed into the public birth records.

Oh, Please!

His stench talks politely the language of a hangman’s knot ,

a tight noose around my neck.

The teasing smell of death.

Grunting with every step, he comes.

Windows open

Light steps hurry away ashamed of youth and health,

heads bowed .

He leaves us for a momentary rendez-vous with scrubs.

Another success story.

He returns.

The tango

with the summer breeze

starts too rushed.

Without skipping a beat he provides the chorus line “ Oh, please”

Oh, please! I add bending too low under the summer breeze.

Living room

Washington Square Park

Live jazz played on a grand piano

Drinking Madman Espresso iced latte.

A mother playing with her daughter as if she were a young, highly educated, white nanny: despite the music.

A badly kempt ghost, the piano man builds time with music and lovemaking blocks

the latter as spare as his dinner.

A dog barked and scratched

A child tripped and fell

I blinked

Sitting and waiting for all to pass by.

Daughterly love

“Why do you think, mom, everyone is out to get you?”

“Not everyone”, my smile stops the wordy defense

Only death, sweetheart,

And even she is not

That intent in getting me.

Pretending

I play the role of a mummy

Covered in palimpsest

Stories handwritten

In magic, invisible ink

Brain, heart, lower organs

All

Eviscerated

To survive

The daily routine

Marzia Rahman is a Bangladeshi writer and translator. Her flashes have appeared in 101 Words, Postcard Shorts, Five of the Fifth, The Voices Project, Fewerthan500.com, WordCity Literary Journal, Red Fern Review, Dribble Drabble Review, Paragraph Planet, Six Sentences, Academy of the Heart and Mind, Potato Soup Journal, Borderless Journal, The Antonym, Flash Fiction Festival Four and Writing Places Anthology UK. Her novella-in-flash If Dreams had wings and Houses were built on clouds was longlisted in the Bath Novella in Flash Award Competition in 2022. Her translations have appeared in several anthologies. She is currently working on a novella. She is also a painter.

What One Generally Sees Inside or Outside of a Classroom

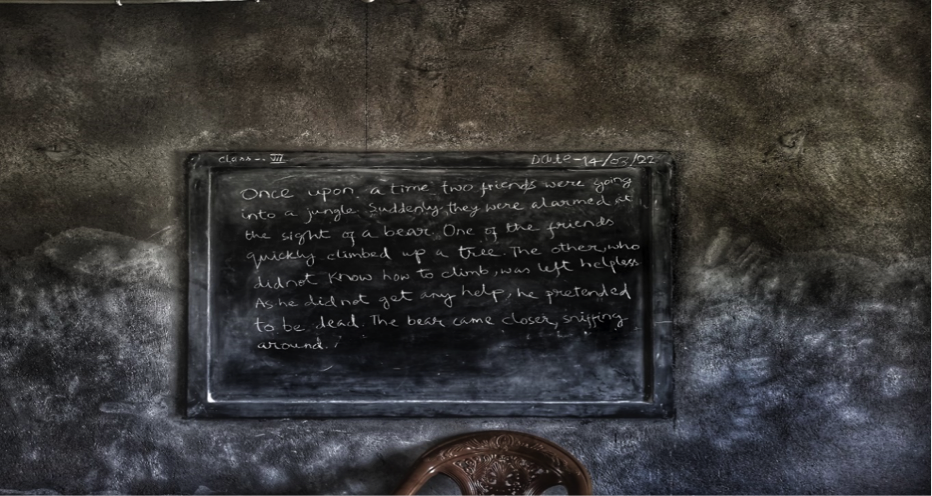

Photo by Aritra Sanyal

A blackboard, with date, month and year written on one side and class and subject on the other side.

A duster. A few white chalks; some whole, a few broken. The broken ones are more useful; students use them to play or draw pictures on the desks or the dusty floor.

A door. Its lock is broken but no one fixes it because it does not need to be fixed. A chair where the teacher sits doggedly and watches over the students.

Rows of tables and benches. A window or two, where a boy or a girl is often found sitting with little or no attention in the class. The blue sky, the horse-shaped clouds, the trees, the green leaves, the grasses and the butterflies hold more charm to them. And one day, this boy or this girl may or may not become a poet who may or may not remember the window.

Boys wear watches. Girls wear ribbons and whisper in each other’s ears, giggling. Boys watch them with the corner of their eyes and try very hard to look indifferent but their hearts hum like bees near the honeysuckles.

A headmaster with more grey hair than black whose retirement is more fun-filled and eventful than his twenty or thirty-years of service.

A math teacher with a complicated expression on his face who gives students complex math problems and hopes they will solve them by themselves.

A science teacher who believes in science more than his marriage and secretly looks for another job in another school, preferably a private one.

An art teacher who dreams of holding a big exhibition in a big city; he falls in love with the new geography teacher who doesn’t understand art. To her, Van Gogh or Picasso are mere names, signifying nothing.

A peon who is slowly and gradually turning deaf; he has been ringing the school bell from time immemorial. He sleeps in a hut close to the school and often hears the chiming of bells in his sleep.

A dog or a cat that roams around the school wags its tail and sits in the sun. The pet has become an indispensable part in the indispensable syllabus of the school.

One or two mishaps, some scandals, a few fights between boys with newly grown moustaches, an expulsion, a source of great amusement. Gossips with long tails.

Final examination. Report Day. Sports Day. Summer break. End of School. The End of Story.

[This piece was inspired by a story titled “What You Usually Find in Novels,” written by Anton Chekhov, and translated by Peter Sekirin. It was featured in The Paris Review (issue 152, Fall 1999)]

The Prayer Room

Photo by Aritra Sanyal

I stand in the middle of a room. It’s empty. I look at the wall before me. Two portions divide the wall like two parts of a story: the beginning and the end. There is no middle, no climax, no closure, no plot. The English fiction writer, E. M. Forster once famously lamented that a novel must have a plot.

A plot shapes a story; it determines how a story develops and unfolds in time! Does a plot define a story too? I wonder what defines a room—its size, structure, colour or history? What history does this room carry? — it used to be a prayer room, that I heard.

The young tour guide with a small red notebook in his hand was showing visitors around the fort; a small group of foreigners with not so colourful clothes and two hippies with the most colourful clothes and hair bands followed him. I was not part of the group; I just happened to be there; I just happened to listen to their conversation. The guide mentioned some prayer room; I didn’t hear the rest of his narrative; I soon got lost in the labyrinth of this place, or was it his words?

I meandered aimlessly for a while, peeked here and there and then passed a long corridor with rose stained glass windows streaming warm tones across the marble floor, before stepping into this room. It has small holes in the walls like closed off windows. A small space inside each hole to store the holy books or maybe the candles.

As a prayer room, this place must have witnessed thousands of prayers and chants, candles must have been lighted here, wishes made, absolutions sought by believers with doubts in their hearts.

No longer a prayer room, the room looks different now; it has a different vibe now. Open to visitors, people come and write names, characters, numbers, equations on the green sandstone in the wall.

I stand close to the wall and stare hard; Ketan, Lucky, Vasu, Rozot on the wall stare back at me. Caught up in the whirlpool of thousands of names, I begin to lose myself, and I seem to enter into a colossal void where there is no beginning or end, where nothing is virtuous or sinful, and where time stands still, and forever. And this is when I finally make a prayer.